Indian egg rice is full of flavor from the cloves, cinnamon, and pepper in it; onion sauteed in lots of butter, or ghee, also adds to its taste. Information on varieties of rice, its health benefits, and my recipe for egg rice are given below.

Background of Rice

Rice has a colorful history; it is thought that its domestication dates back perhaps to 5000 BC in South China, which was an independent country at the time. It began to be cultivated in India’s Ganges Delta, from about 2000 BC forward. 1 For more details on its history, see Riso Pilaff (Italian Braised Rice).

Oryza sativa and Its Two Subspecies

There are thought to be more than 100,000 varieties of rice in the world. Its Latin name is Oryza sativa, which has two traditionally recognized subspecies. The first is Indica -generally grown in the lowland tropics and subtropics, having a lot of amylose starch and a long, firm grain, which needs more water and time to cook. The second is Japonica, which can be found in temperate climates such as Japan, Korea, Italy, California, and in the tropics (such as Indonesia and the Philippines, where these rices are sometimes known as javanicas). Japonicas have much less amylose starch and produces a shorter, stickier grain. Some rice varieties fall in between these two subspecies, but the more amylose starch in the variety, the more the rice will retain its structure; thus, more water, time, and heat are needed to cook the rice. 2

Common Categories of Rice

There are common categories of rice: long-grain, medium-grain, short-grain, and sticky rice, along with the two distinctive categories of aromatic and pigmented rices. I generally cook with brown basmati rice from India, which is one rice in the distinctive category of aromatic rices; among other well-known aromatic rices are Thai jasmine and U.S. Della. The other distinctive rice group is that of special pigmented rices, in which the bran layer produces different colors-there is red, black, and purple rice.3

Most Chinese, Indian, and U.S. rice is long-grain rice. This category of rice has a relatively high proportion of amylose at 22%. (Amylose is one of the two types of carbohydrates found in rice; the other type being amylopectin, which is found in sticky rice.) With the high proportions of amylose, long-grain requires the most water for cooking (water to rice by volume is 1.4 to 1). These long-grained Indicas are an elongated shape, with a length which is 4 to 5 times its width. When cooked they produce separate grains, which are firm when cooled and hard when chilled.4

Medium-grain and short-grained japonicas are used in Italian risottos and Spanish paella; Medium-grain rices have a 15-17% amylose content; thus, they need less cooking water, and they produce tender grains that cling to each other. Short-grain rice is nearly the same in width as it is in length, and it is otherwise similar to medium-grain rice. These short-and medium-grain japonica rices are heavily used in north China, Japan, and Korea.5

Sticky rice, a short-grain rice, is also known as waxy, glutenous, or sweet rice, though it is not sweet, but often used in sweet Asian dishes. It has a starch that is practically all amylopectin; thus, it requires the least water for cooking (water to rice by volume is 0.8 to 1). It is very clingy when cooked and easily disintegrates in boiling water; for this reason, it is often soaked and steamed. It is widely used in Laos and northern Thailand, often in sweet dishes, though it is not sweet in itself..6

Brown Rice and Its Health Benefits

Brown rice is any of the long-grain, medium-grain, or aromatic rices above, which are left unmilled,; thus, the bran, germ, and aleurone layers are kept intact. In this form, rice takes two to three times longer to cook than its polished counterparts of the same variety. It has a chewy texture and nutty aroma. White rice is brown rice, with the bran layer polished away, leaving it with only one-third of the fiber.7

The bran layer in brown rice contains antioxidants, in the form of three phenolics, which are also present in the germ. Many of these are lost, when the bran layer is stripped away in the making of white rice. When they are present, they can aid in reducing free radicals from attacking the cells; thus, they may help to prevent cancer. Also, fiber found in the bran layer may lower your cholesterol, which is believed to reduce the chance of heart disease and stroke.8

Brown rice can aid in digestion, because it is high in insoluble fiber, which doesn’t break down in the digestive tract; thus, it adds bulk to stools and therefore may produce regular bowel movements. Along with this, the fiber in rice makes one feel full; thus, it can help in weight control.9

Brown Rice May Help with Diabetes

Brown rice has a glycemic index of 64, as opposed to that of white rice, which is 55; therefore, brown rice may be helpful with managing diabetes. It is thought that fiber found in brown rice doesn’t raise blood sugar levels, but rather it helps to slow down the absorption of its sugars; thus, it may be beneficial in stabilizing blood sugar.10 It is believed that long-grain rice, being higher in amylose, is better for keeping blood sugar levels from spiking. 11

Brown Rice-an Insoluble Fiber

Soluble fiber found in simple carbohydrates, ferments in the stomach, causing bloating and gas. This soluble fiber is digested by bacteria, when it passes into the large intestine, and this releases gases which cause flatulence. (On the other hand, brown rice actually feeds the good bacteria in our GI tract!12)

Insoluble fiber in complex carbs, such as brown rice, remain undigested as they pass through the GI tract; thus, constipation and gas may form. White rice is a simple carbohydrate, which the body breaks down quickly, as opposed to complex carbohydrates that are digested much slower. Too many refined carbohydrates can lead to inflammation and bloating. In this way, the complex carbohydrate, brown rice, is a healthy choice, especially if it is replacing white rice.13

Enjoy the simple recipe for egg rice below.

References

- Reay Tannahill, Food in History (New York: Three Rivers Press, 1968, 1973), pp. 40,113.

- Harold McGee, On Food and Cooking (New York: Scribner, 1984, 2004), pp. 472, 473.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- https://www.webmd.com/diet/health-benefits-rice#1

- Ibid.

- https://draxe.com/nutrition/insoluble-fiber/

- Ibid.

- https://www.eatthis.com/news-what-happens-body-eat-rice/

- https://draxe.com/nutrition/insoluble-fiber/

Egg Rice Recipe Yields: 8 servings. Total prep time: 40 min/ Active prep time: 10 min. Note: add chicken and green peas for an entree.

1 1/2 c rice (Indian basmati brown rice works well; available at Trader Joe’s.)

1 med yellow onion

4 tbsp butter or ghee (Get easy, quick directions for making ghee at Asparagus.)

4 whole cloves

1/4 tsp cinnamon

1 1/2 tsp salt

1/4 tsp freshly ground pepper

4 lg eggs, beaten

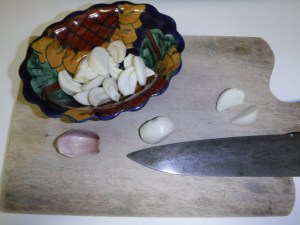

- In a saucepan, with a tight-fitting lid, bring 3 c water to a boil. Before boiling, add to water: cloves, cinnamon, salt, and pepper. See photo.

- When water is boiling, add 1 1/2 c rice and bring to a second boil. Cover and reduce heat to simmer rice. Cook for 35 minutes, or until water is absorbed. Remove from heat, take out cloves, which will be on top, and fluff rice with a fork.

- Meanwhile, dice onion small.

- In a skillet, melt butter or ghee. Add onions and cook until they just begin to turn a golden color-see photo below.

- Add beaten eggs, and cook to a soft scramble, set aside.

- When rice is done, mix in egg/onion mixture; see photo at top of recipe. Serve it forth-delicious!